Water Treatment 101: Viruses

Originally published on February 12, 2015.

Viruses take the cake as tiniest of the waterborne disease-causing microorganisms—smaller than both protozoa and bacteria. These nasty little bugs are also the least understood by scientists, and cause the greatest range of symptoms across infected individuals. The good new is, in North American backcountries, viruses are typically considered much less of a concern than the other pathogenic threats.

Why do viruses poses less of a threat in North American wildernesses?

Viruses are very species-specific. In other words, they don’t infect just any host they come in contact with. If you catch a virus, its source was most likely another human being. Therefore, human-specific viruses tend to be less present in settings where there’s little human traffic. In addition, in developed regions—like much of North America and Europe—advanced sewage systems and generally good hygiene practices have greatly reduced the risk of viral outbreaks.

But in much of the developing world, viruses still pose a significant risk. Where sanitation is poorly maintained, uncontrolled sewage can contaminate drinking water. For international travelers, this risk is compounded by the fact that good medical services can be hard to come by should you get sick. Most viral infections aren’t life threatening in healthy adults, but the ability to rehydrate your body with safe drinking water is critical.

Even as a traveler in the backcountry, however, you must be observant of your surroundings, and recognize where others may not have practiced clean tactics. Popular camp spots tend to be higher-risk zones. When people neglect to dispose of their waste properly, viruses can be present in the natural water sources.

Viruses are indeed extremely small. Most species fall within 0.01 – 0.3 microns in size. Microfilters typically don’t remove them. To treat them, you must use a purifier (or boil your water). By definition, a purifier removes all three waterborne threats: protozoa, bacteria and viruses. If you’re traveling to a country where access to safe drinking water is a concern, consider bringing a purifier as your treatment tool of choice—or as a mandatory addition to a microfilter.

How are viruses spread?

Viruses are spread primarily through fecal matter. They can advance quickly through backcountry campsites when people don’t wash their hands sufficiently, and make their way onto food and into water sources. In countries where drinking, bathing and well water are vulnerable to sewage contamination, viruses can spread rapidly through communities.

Viruses can survive for very long periods of time, but can only reproduce in the living cells of a host. Which is why they need you.

Which are the most common types of waterborne viruses?

In North America, norovirus and rotovirus are the most prevalent pests. If you’ve ever gotten a bad case of “food poisoning,” there’s a chance you were playing host to—and dealing with the consequences of—one of these microorganisms. Hepatitis A is also of concern in many developing countries.

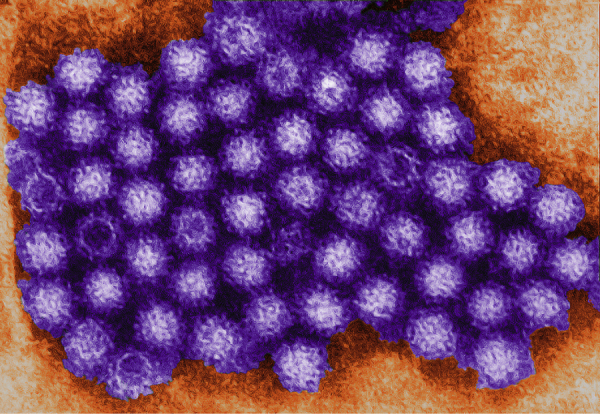

Norovirus / Norwalk

Norovirus, also known as Norwalk virus, is an environmentally hardy microbe. In addition to spreading through food and water, it can pass via person-to-person contact. It withstands disinfectant hand gels used to kill bacteria and it’s very contagious. It takes only a few to make you sick—scientists estimate a single particle to about 10, even in healthy adults. Once in you, it causes your stomach and/or intestines to inflame, resulting in nasty symptoms.

Symptoms include shooting or projectile vomit, watery diarrhea and cramps. These typically start 24-48 hours after exposure. Low fever, headaches, muscle aches and chills can also occur. Healthy adults usually get better after a day or two. But the virus can continue to be shed in bowel movements. People with weaker immune systems tend to experience more severe symptoms. About 30% of people show no symptoms at all, but can still infect others.

Drinking plenty of liquids to replace fluid loss and prevent dehydration is crucial.

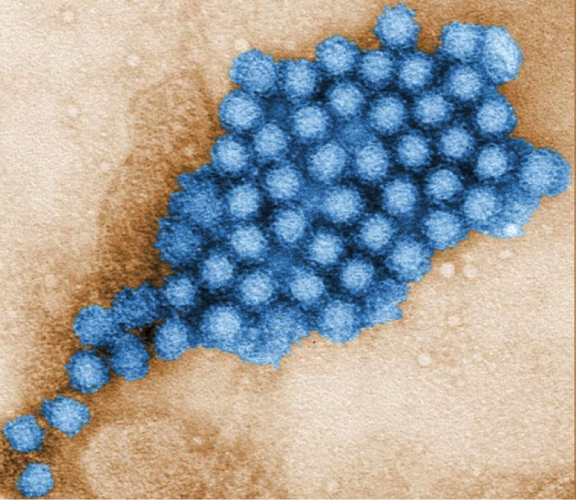

Rotavirus

Rotavirus is of particular concern for infants and children. It’s one of the main culprits of diarrhea and dehydration in this age group, causing around 500,000 deaths each year in children 5 and under worldwide. In 2006, a rotavirus vaccine became available for children in the U.S.

The infective dose for rotavirus is estimated to be 10 to 100 particles.

Symptoms in healthy adults start to show in about 48 hours. A fever of over 101°F is usually the first indication, followed by vomiting and watery diarrhea. Symptoms usually pass in 3 days to a week. Children and those with weaken immune systems should seek medical attention.

If fluids and electrolytes aren’t properly replaced, the illness can progress to life threatening.

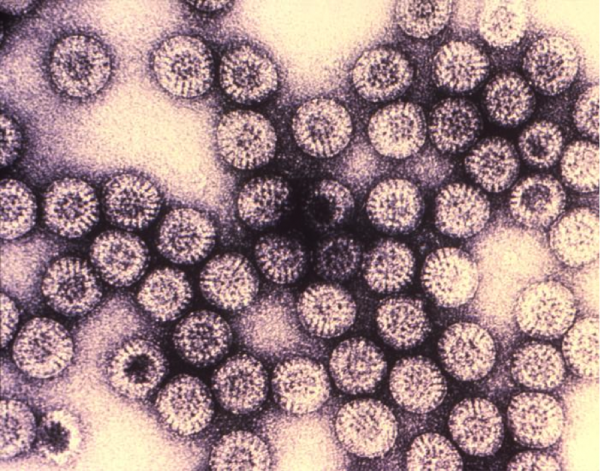

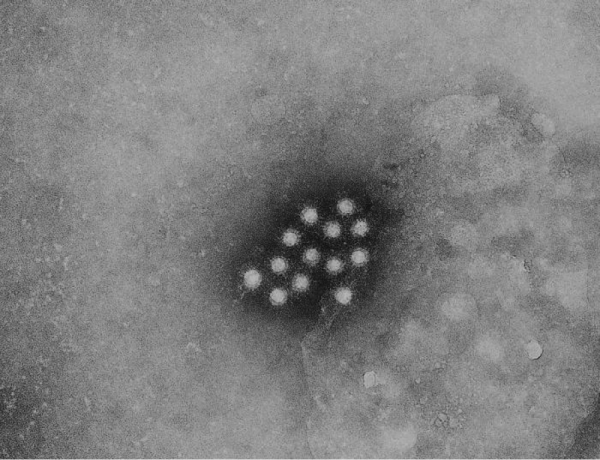

Hepatitis A virus

Hepatitis A isn’t considered a major threat in the undeveloped water sources of North America. But it is a concern in countries with poor sanitation, particularly parts of Africa, Asia and South America. The virus causes the liver to inflame, affecting its functions. In rare cases, it can damage the liver enough to cause death. Scientists believe the infective dose of Hepatitis A is around 10 to 100 particles.

Symptoms may include fever, reduced appetite, vomiting, diarrhea, muscle aches, and jaundice, which is yellowing of the skin and eyes. The gastrointestinal symptoms usually show in 2 to 4 weeks and jaundice generally appears 5 to 7 days after. Sometimes, jaundice is the only symptom. In healthy adults, the disease typically goes away in a week or two. Some people don’t show any symptoms at all.

Diagnosis:

To determine which virus you’ve contracted, your doctor can run lab tests. Depending on your symptoms they may ask for a blood, stool or vomit sample to analyze.

Treatment:

Most healthy people who are diligent about replacing the fluids and electrolytes lost will recover without medical treatment. Antibiotics do not work on viruses. Children, elderly individuals and those who are immunocompromised should see a doctor right away as viral diseases can progress to severe states quickly in these groups.

How to Remove Viruses from Your Water:

Whenever viruses are of concern, think: purifier. Microfilters typically only remove parasites (protozoa) and bacteria; they’re generally sufficient in North American backcountries. But if you’re worried that there could be a viral risk where you’re going, bring a purifier—either in the form of a device or an agent, like Aquatabs®. However it’s important to remember that UV light devices and purifying tablets do not remove sediment and particulates in the water, so you’ll typically have to filter the water first before using these treatment methods.

U.S. EPA requirements call for removal or inactivation of greater than 99.99% of viral particles. The MSR Guardian purifier delivers this level of protection. As do Aquatabs. Tablets also make a good backup in the field if you come across a hairier situation than you were expecting.

As carriers of our own viral offenders, it’s important that all backcountry, international and adventure travelers practice good hygiene to protect ourselves and others from infection. Always purify your water if there’s a chance that viruses are present. There’s no easier way to ensure that all you bring home from your grand adventures are stories and pictures to share.