Water Treatment 101: Bacteria

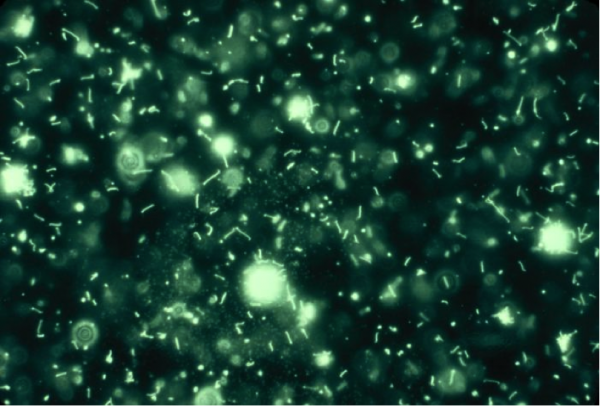

Bacteria are everywhere—on you, in you, in the soil, and yes, even in the wilderness’ cool, refreshing water sources. In fact harmless species of these single-cell organisms exist naturally in the backcountry’s rivers and pools.

But humans and animals can carry harmful bacteria as well, and spread these pathogens to the water, making it risky if you happen to drink from the wrong place at the wrong time. Some of these bacteria are the same notorious headline grabbers associated with foodborne outbreaks or epidemics after natural disasters. We’ll discuss those and others, but first a few general facts.

In the North American backcountry, we believe the likelihood of contracting a bacterial infection isn’t particularly high. Still, there’s always a chance—and the consequences are no fun. Filtering or treating your water is always recommended. You never know if that cool sip you’re about to take after a hot day on the trail is contaminated from someone or something just up stream.

On the microscopic scale of pathogens, bacteria are considered “medium” in size. Most species are between 0.2 – 1 micron, making them typically smaller than protozoan parasites and larger than viruses. They’re also less region-specific—almost all types can be present in water sources worldwide.

The symptoms of bacterial diseases are unpleasant to say the least, but most are not life-threatening in healthy adults. Of course, prevention is always the wise traveler’s cure.

How are bacteria spread?

Nearly all bacteria are spread through the fecal matter of infected humans and animals. When transmitted to water, bacteria can reproduce. For these reasons, good hygiene practices, even in what may seem like the pristine backcountry, will help prevent you from ingesting infectious cells. The presence of stock animals in nearby grazing lands only increases the risk.

How do bacteria species differ?

All bacterial illnesses produce similar symptoms, and most healthy adults recover from all without treatment. Their differences lie in the number of cells it takes to get you sick, how quickly symptoms appear and how long they last. These variances are related to the species, but the strength of your own immune system also determines what you experience.

Which are the common bacteria to be aware of?

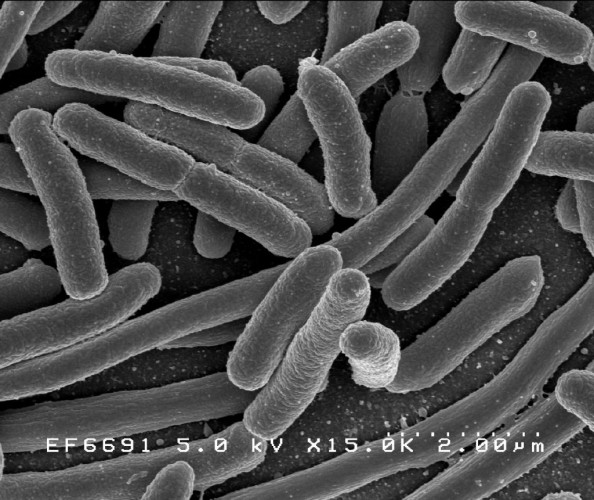

E. coli

E. coli (Escherichia coli) gets a bad rap from the media, but many strains are harmless and some are even important natural inhabitants of your intestines. Of the pathogenic types, the kind you’ve read about in the news (VTEC) is much more serious than what you’d likely pick up from untreated water (usually ETEC), which causes “traveler’s diarrhea.” In healthy adults, it takes about 10 million – 10 billion ETEC cells to make you sick. While that sounds like a lot, a mere 25 mL of water can contain 10 million cells. Children and people with weak immune systems may require less.

Symptoms occur about 26 hours after infection and are usually rice-water-like bowel movements, cramps, fever, nausea and dehydration. Most cases last only a few days, but severe cases can endure for more than 3 weeks.

Shigella

Shigella is transmitted only through human feces (and that of some primates). Therefore it’s a concern in places that see greater human traffic. As few as 10 to 200 cells can make you sick with shigellosis, but the disease is usually pretty mild in healthy adults and passes without medication. However, rare severe cases are treated with antibiotics. Some people can be infectious without showing any symptoms.

Symptoms appear within 8 to 50 hours and are typically diarrhea, fever and cramps, but can include vomiting, and blood, pus, or mucus in stools. In healthy adults, symptoms usually go away after 5-7 days.

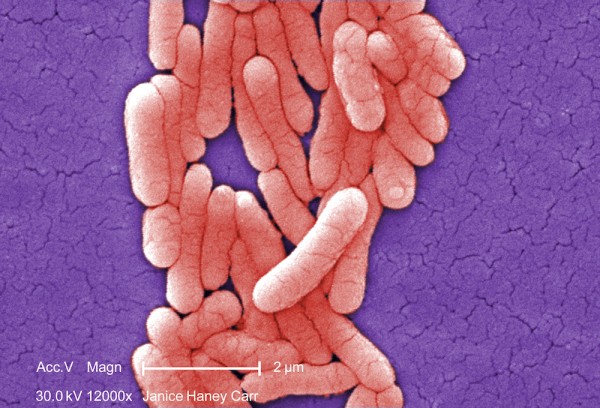

Salmonella

Depending your health, just a single salmonella cell can make you sick. The symptoms from this fierce little bug can show in as little as 6 hours, and up to 72. Although the disease passes within 4 to 7 days without antibiotic treatment for most, it has been known to be life threatening even in healthy individuals.

Symptoms include diarrhea, cramps, nausea, vomiting, fever, and headache. Replacing fluids and electrolytes lost through diarrhea and vomiting is critical.

Cholera

Caused by the bacteria Vibrio cholera, cholera is rare in the U.S. these days—the last major outbreak was 1911. But the disease continues to present an increasing mortality threat in developing regions where sanitation is poor, especially Africa, Southeast Asia, and Haiti. According to the CDC, 3-5 million cases of cholera occur annually worldwide, with more than 100,000 deaths. This is important for global travelers, who should research where the risks lie and take the proper precautions.

It takes a good 1 million cells to make a healthy person sick. Symptoms appear a few hours to 3 days after exposure and last a few days.

Symptoms include rice-water-like diarrhea, and vomiting. Immediate treatment through rehydration of fluids and salts is crucial but usually results in easy recovery. According to the CDC, a prepackaged mixture of sugar and salts mixed with water is used throughout the world to treat diarrhea. Without rehydration, however, cholera can be deadly.

Diagnosis:

Because their symptoms are so similar, diagnosing a particular bacterial disease requires a stool sample be provided to your doctor for lab tests.

Treatment:

The biggest concern of any bacterial disease is dehydration, and in severe cases dysentery, caused by diarrhea and vomiting. Replacing fluids and electrolytes quickly is usually all that’s needed to treat healthy adults. But individuals with weak immune systems should seek medical attention. Without rehydration, cases can become life-threatening.

Removal:

Because of their size, most bacteria can be easily removed by filters that meet accepted standards for bacterial removal. They can also be treated with oxidants, UV and boiling. However, only filtering will remove any dirt or debris also present in the water. Because particulates can shield the microbes from UV light rays, at MSR, we recommend filtering your water to remove bacterial threats. Or at least, filtering before using UV.

The U.S. EPA calls for removal or inactivation of 99.9999% of bacteria in drinking water. All MSR microfilters and purifiers meet this standard, including the MiniWorks, SweetWater and AutoFlow systems.

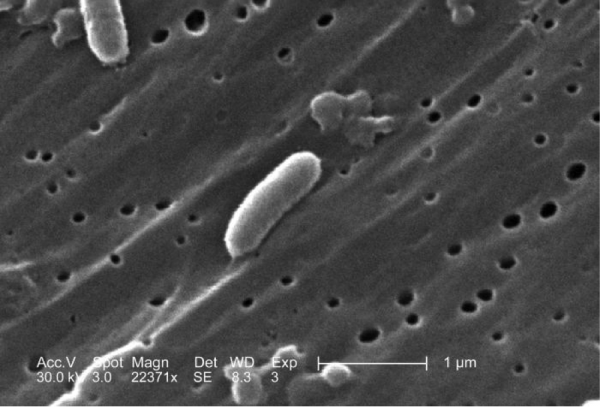

Leptospira: An exception to the rules

If you’ve tried to backpack in Hawaii or another tropical region, you may have read about Leptospira. Lepto is a bacterium that exists worldwide, but is most prevalent in hot, wet climates. It’s spread to humans from the urine of infected animals, such as rats, pigs and cattle; rarely from human to human.

Lepto is of special concern because it’s smaller than most bacteria. It ranges from 0.1-0.3 microns in diameter. Its unique size and shape—long and skinny—makes it capable of sneaking past some filters some of the time. For it to slip through, it must line up in perfect orientation with a pore in the filter membrane. This is a pretty rare event, but because there is a slight possibility, most filters don’t claim to reliably remove it.

Where lepto is of concern we recommend using the Guardian purifier, or Aquatabs® purification tablets to kill any remaining threats after you’ve filtered your water.

Symptoms of Leptospirosis can appear within 2 days to 4 weeks after exposure and may come in two phases:

First, fever and chills, along with headaches, muscle aches, vomiting, and diarrhea, after which the individual may show signs of recovery. If a second set of symptoms show, the case has advanced in severity and kidney or liver failure is a risk.

Symptoms usually go away after a few days to 3 weeks, or can last even longer. Antibiotics taken early on will help expedite recovery. A doctor should be consulted for the proper prescription.

Lepto however is not a concern in most North American backcountry settings. Here, a quality filter rated for bacteria will usually suffice to ensure safe drinking water. If viruses are a concern, we recommend also using a purifying agent. Remember, it’s a liquid landscape out there, where water quality is always fluid. Your first drink might be fine, while the next can offer you much more than simply sweet hydration.

All photos courtesy of CDC.