Hiking a Route vs. Hiking a Trail: Part 2

By Renee Patrick

Oregon Desert Trail Coordinator for the Oregon Natural Desert Association

My heart lurched as I scanned the snow-covered forest floor looking for any hint of a path through the trees. The hiker whose footsteps I was following knew where they were going, right? When those footsteps made an unexpected turn in the snow, doubt crept in. Had the footsteps lead me astray? Was I lost? I pulled the map from my pocket, determined that, wherever I was in this thick forest, if I headed north I would intersect a road…eventually. I followed my compass bearing for almost an hour before crossing a dirt road draped with melting patches of snow. Yes! I did it! Now I set to the task of finding my next landmark to figure out where on the map I had ended up. I’m not lost! Just not exactly sure where I am…

My backcountry navigating skills were put to the test again and again when I hiked the fledgling Arizona Trail nine years ago. Even though I was hiking a developing trail, many sections required route-finding. In times like these having the skills to find yourself again is crucial.

If you want to hike a route, you need a solid backcountry skill set. Developing those skills will open up new possibilities for spending extended time in the backcountry.

In part 1 of this series, we looked at the differences between a route and trail. Now, we’ll look at how to acquire the route-finding skills needed for that off-trail hiking.

As the Oregon Desert Trail Coordinator, I spend a lot of time helping people feel comfortable and confident with off-trail travel. For this piece, I polled some of the most accomplished route creators and hikers I know for their advice. Liz “Snorkle” Thomas, Cam “Swami” Honan, Justin “Trauma” Lichter, Sage Clegg, and Paul “Mags” Magnanti all have extensive experience and play an active role in educating hikers new to the trails and the backcountry.

How to develop your skills

- Take a navigation class: Learning how to navigate with a map and compass from an experienced instructor is a great start. Your options include watching online tutorial videos, taking a class at your local outdoor store, and signing up for a guided field trip.

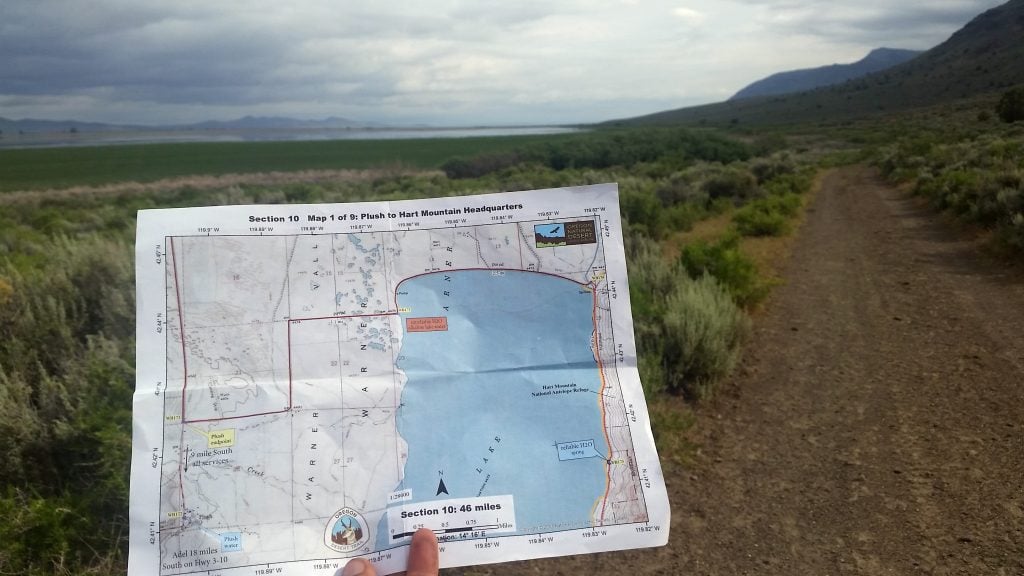

Photo by Renee Patrick

Trauma took an outdoor education class in college that had him wandering around the canyon country of southern Utah for three months, for which he got college credit. Sage learned to use a map and compass at 14 when she enrolled in an Outward Bound course. Mags took an Appalachian Mountain Club course in “the wild, remote lands of Rhode Island” just prior to his AT thru-hike.

- Practice: “Once you feel comfortable with the basics, it’s time to use those skills,” explains Mags. Practice your navigation. Then practice again BEFORE you head out on a challenging route.

- Practice on trails: “To learn, I always carried a map on hikes that are on trails, and frequently checked the map to make sure I always knew about where I was,” Snorkle says. “Following along on the map, I got a feel for how topo lines translated into hills or ridges so when I really needed those skills, like on cross-country sections or when the trail disappears, I had a better idea.”

- Practice NEAR trails or very visible landmarks: “Practice in a place you can fail,” Sage suggests. “Go off-trail between two easy-to-find ‘handrails’ like a river and a road, or between two established trails. If you get off course you can always bail to familiar turf by traveling towards the handrail.”

- Practice micro-navigation: The art of making small route choices on the ground, or “micro-navigation” is just as important as the skills you learn in navigation classes. “What is the best way to get around that gap before the pass? Should I go left or right on the talus slope? This type of navigation mastery can only come with experience,” Mags explains.

- Practice in an urban setting: Snorkle suggests, “Put together a complicated walking route with lots of turns, go for a trip, and practice with a paper map. If you’re really lost, you can always check your phone or find a ride home.”

- Anticipate the terrain: Beyond knowing where you should be on the map now, look ahead and predict what you will do next. Will you cross a creek right before you need to make your turn? You can be on the lookout for the creek that will indicate your next move. Study your maps right before your hike to get a lay of the land, and repeat at each break.

- Go with more experienced people: “I started hiking off-trail before I was ever a thru-hiker,” Snorkle says. “I went with more experienced hikers, watched what they did and learned from them. I followed along on my own maps, made educated guesses, and then checked in with them for confirmation.”

- Learn on maps before GPS: GPS devices and smart phones have become incredibly common and utilitarian, especially when hiking off-trail. However, it’s still important to have the analog skills of map reading and navigating. Devices can break, technology can lead you astray; it’s vital to always carry paper maps and know how to use them.

- Scout the route before your hike: Swami says, “I’ll go over my proposed route several times, identifying notable landmarks, challenging stretches, potential camping areas and possible exit routes in case of an emergency.” If your route has a GPS track, upload it to Google Earth and review the trip with detailed satellite imagery.

Photo by Sage Clegg - Build skill development into your objective: “Each adventure can be a learning experience, as much as it is an opportunity to visit a new place,” Trauma explains, “I try to add a skill that I can improve on into the core goal for each trip I take. This also helps create a challenge that keeps me interested and inspired.”

Other considerations

- Take extra safety precautions: “Prior proper planning prevents piss poor performance,” Trauma advises. Err on the side of caution regarding the amount of food, water, clothing you will carry and the distance you plan to travel per day. On routes, these variables are often quite different from backpacking on an established trail. “I leave a detailed description of my proposed route with friends or family before setting out,” Swami says. “Consider carrying a personal locater beacon, such as a SPOT or Garmin inReach.”

- Be aware of private public land issues: It is your responsibility to know the rules and regulations on public lands, Each land management agency has different protocols regarding caching, permits, access and more. Do your homework. It is also your responsibility to know how to avoid going on to private land. Not all fences indicate private land, and not all private land is fenced. Many GPS apps have private land layers, and hunting unit paper maps often show private land parcels.

Photo by ONDA - Be willing to adapt: “Mother Nature doesn’t have a copy of your itinerary,” Swami likes to say. “The keys to hiking a route are preparation, adaptability and objectivity. If you aren’t sure that a particular area will be navigable, have a Plan B. Never be too wedded to a particular course.” Carry a map of the entire area you’ll travel through, so you’re able to find a new route if plans change.

Once you have the experience and skill level to head off the beaten path, being successful in remote backcountry settings falls to making good decisions. Listen to your body, observe the terrain and weather, carry the resources you need to make route decisions in the field, and remember to enjoy yourself! Taking a rest day, or a side trip for ice cream, are good decisions if they keep your morale high and your feet happy.

When you’ve mastered your backcountry skills, I hope to see you out on the Oregon Desert Trail! This 750-mile route through the most scenic places in Oregon’s high desert will challenge – and reward – you.

You might also like: The Thru-Hike You’ve Never Heard Of