Bringing Climbing to an Island Once Abandoned

Words by MSR athlete Nina Caprez, photos by Jimmy Martinello

I dream a lot. Almost every morning I wake up and remember, for a moment, dreams from the night before. Some say it’s a way for the subconscious to process. Maybe I don’t have enough down time to do it any differently.

I had dreams my first days in Makatea, then they disappeared. I guess, there, I was living the dream.

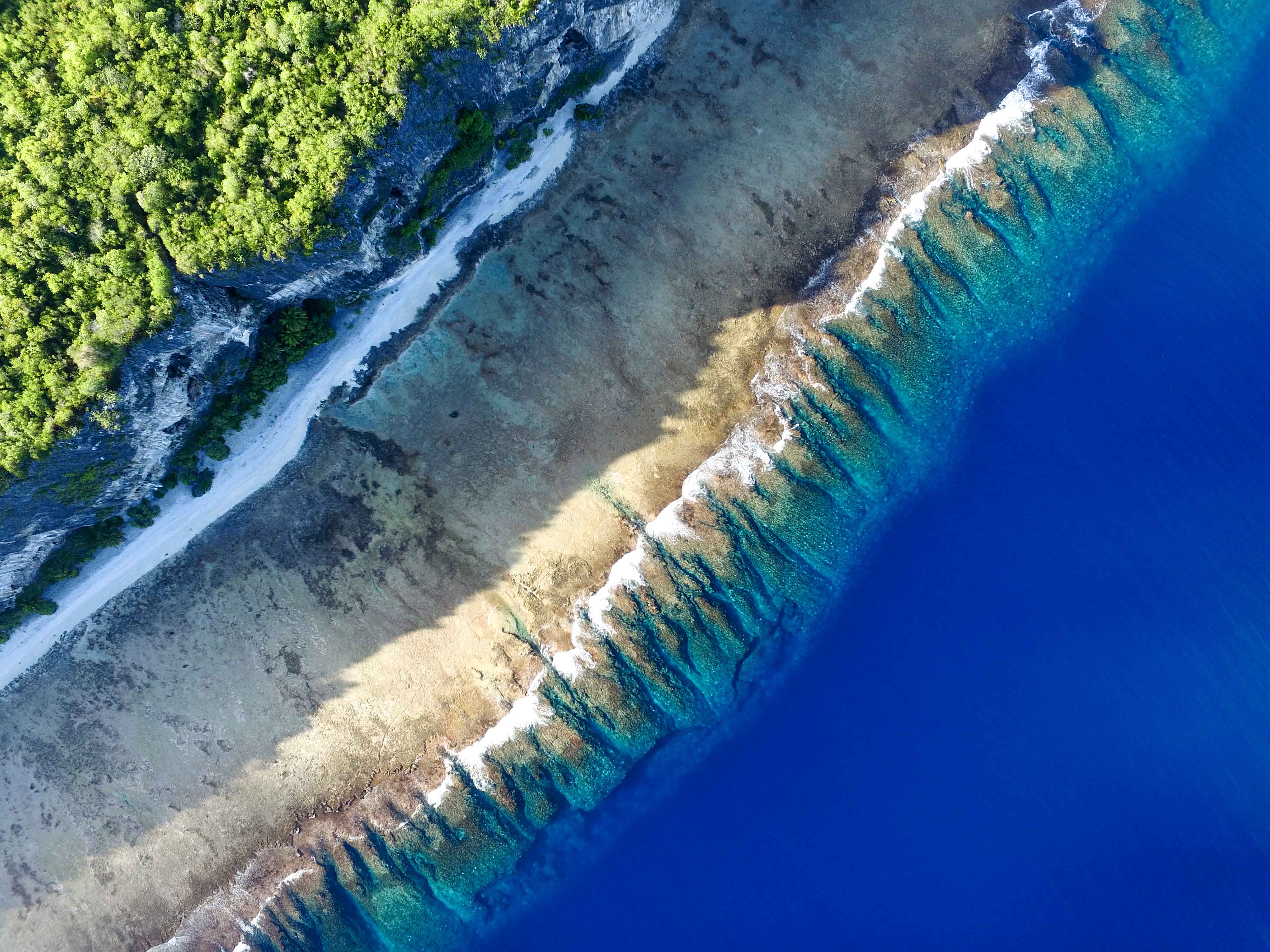

Climbing, like many outdoor pursuits, brings you to places you couldn’t imagine existed. Makatea is one of those. A tiny island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, it’s a mere 6 km by 4 km and part of the French Polynesia.

The atoll is shaped for climbing, with 80 m high cliffs around its perimeter. The only way to get there is by boat, a day of sailing from Tahiti when the sea is fair, or longer and wilder when it’s not (which is what we got).

In the 60s, some 3,000 people lived on the island, working in a mine. The island was rich in phosphate and for some years, money was flowing from the natural resource.

Then, the mining came to an end and work moved on. The mines, the houses, the shops, the trail system, the port… all since abandoned to rust and decay.

The 80 people still living on the island are marked by its history, but nature has since taken over and the jungle hides most of the mining structures. It covers many things, except the damage done to the island’s people.

Our mission was to bring climbing, caving and other outdoor activities to the island and help build eco-tourism as a viable resource. We’d brought together a good crew and were working closely with the mayor’s son, Hai Tapu, who is himself a climber. Years ago, he’d recognized his island’s potential, but in Polynesia, everything moves slowly. Now he had 10 of us to help for an entire month, equipped with our drill machines and a few hundred bolts.

In the month before I left, I had doubts. What if the project failed? What if the climbing was dull? What if nothing happened aside from watching a few old fishermen fish? At some point I simply had to trust the experience.

I’d pictured our crew arriving on this remote island, living from what mother nature had to offer and camping in the total wilderness. But the 80 or so people are connected to the rest of the world in their own way. Despite the rich soil (there are coconut trees everywhere), only a few people grow things. Once per month, a ferry arrives from Tahiti to deliver food. The community is made up of modern houses and a school.

We began our route-setting project next to the island’s harbor. We camped at night and ate coconuts around the clock.

The sea cliffs here offered an excellent playground. We opened two new sectors, on rock similar to what you find on Kalymnos or Turkey. We bolted in the morning until noon, then the sun hit the cliff. After a short nap, we explored the island’s incredible nature. The first obvious thing to do was go snorkelling. Among the pristine coral reefs, we swam with what seemed like billions of fishes, a few turtles and many curious sharks.

The sea is a big part of Makateas’ culture and daily life. We saw their top spear fishermen in action. The harbor is big gathering zone for the community and playing with the children helped us get to know them better.

After 10 days, we moved camp to the other side of the island. Here, the wind and storms hit straight-on, which makes the place so wild and beautiful. The rock is also different. We found 40 m pure blank walls, with perfect pockets and cracks. Above the sea, we equipped routes on steep and perfectly shaped rock—quality far above what we could have ever expected.

Given the abundance of birds living in these cliffs, we payed careful attention when choosing the cliffs we wanted to bolt, not near nests.

In addition to opening new routes, we developed a school program with the kids. We taught them about global water scarcity, resource conservation and caring for our planet. Every day, a new climber would add his or her thoughts to the conversation. On my day, we planted three mango trees and created a play, which the kids showcased at the end of the month.

The cherry on top of this crazy month was the event at the end. Two hundred people arrived from neighbouring islands to experience all the outdoor activity the island has to offer. For four days, we guided groups through different climbing sites, and went caving. We tested the new via ferrata that others had installed and a new zipline. We gave tours of the old phosphate mines, which look today like an enormous battlefield.

Every night, people played guitar and sang around the campfire. The entire village came out.

I was amazed to see the evolution from our first day to that last. Introducing something new to the island, even something positive, had felt strange. But seeing all these joyous people celebrating the beauty of nature and sharing this great feeling of living something unique, made it all feel so right.

Back in Europe, I started dreaming again. Our busy daily life, with its information overload, its lights and noise, was too much for my brain to process. So my subconscious had to start working again. Sometimes I think Makatea was only a dream. I forget how that deep calm felt. But, like my dreams each morning, I try hard to remember.