Op Ed: Recreation at Risk without Public Land

By Renee Patrick, Oregon Desert Trail Coordinator

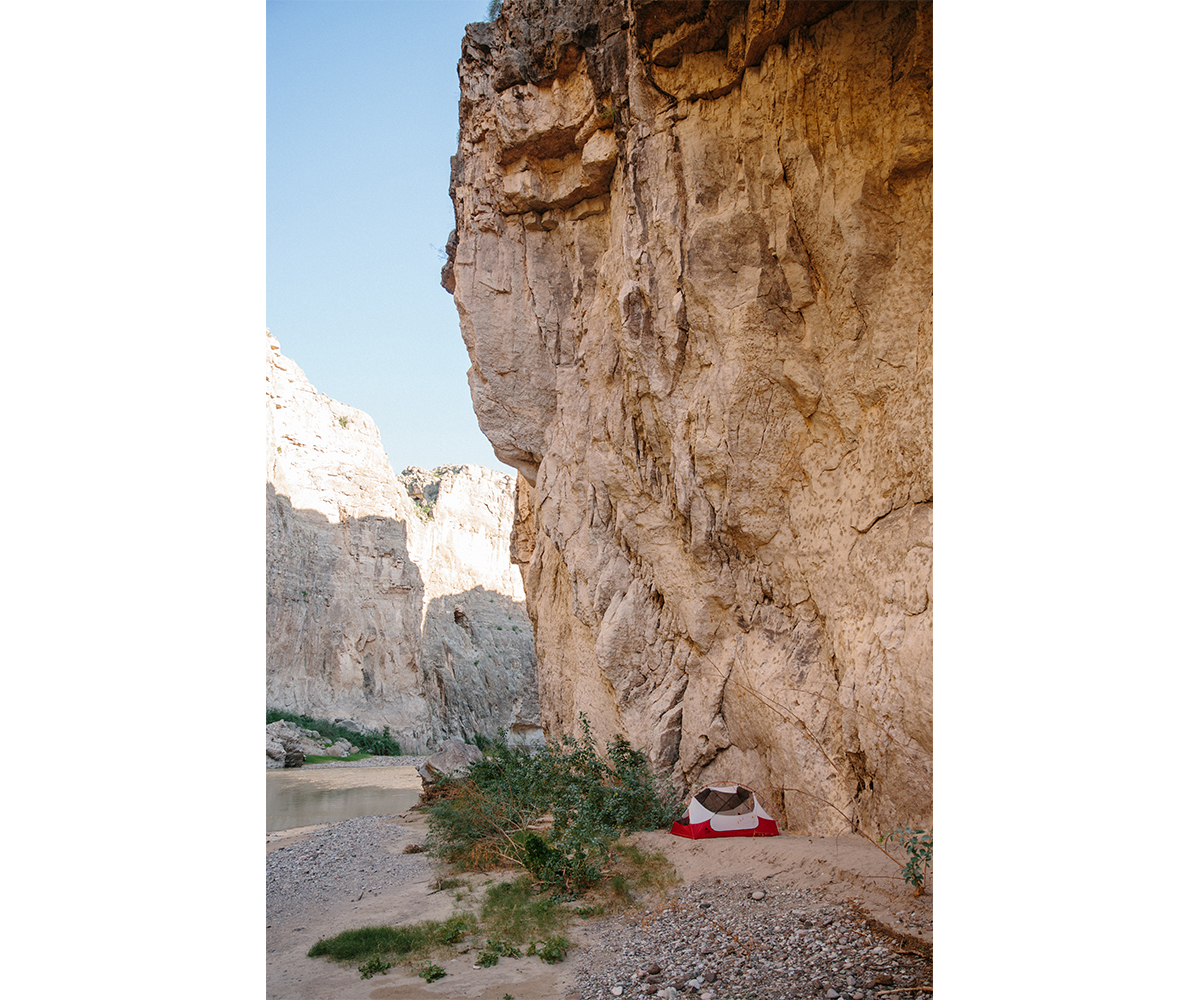

What do hikers, mountaineers, climbers, mountain bikers, rafters and skiers have in common? We need rivers, trails, mountains and that sweet craggy rock; we need remote and wild places in order to have our adventures, make first ascents or descents, and explore our physical limitations.

Now, much of this is in jeopardy with the push to sell, give away or exploit our public land. This public land belongs to all Americans, a legacy that is now at risk.

Since I began backpacking long trails 15 years ago, I have hiked through more national forests, wilderness areas, national parks and Bureau of Land Management lands than I can count. I’ve literally walked across more than 10,000 miles worth of public land. I fell in love with the freedom found in exploring remote corners of our country, sleeping in the dirt, swimming in the rivers and reveling in the fact that my body was capable of such feats.

What I hadn’t considered as I planned adventure after adventure was the elemental framework that creates the foundation for each of these long-distance trails: the public land used to design them. I sought to walk unencumbered across the country, but had given little thought to what made routes like the Pacific Crest Trail and Arizona Trail possible.

Today, it is more important than ever to start advocating for the future of our land. Beyond recreation, there are plenty of other benefits tied directly to public land: increased economic growth for communities close to public land (Headwaters Economics, West is Best study), enhanced quality of life, climate change resiliency, energy production (increasingly in the renewable energy field), wildlife habitat and healthy ecosystems that support clean air and water.

What endangers these lands and puts these benefits at risk? Local and national governments have engaged in initiatives that encourage ceding much of America’s public lands to the states – a move that special interests have pushed in state legislatures across the West. Weaker protections at the state level make it easier to sell our public lands off to private parties and developers. It’s a foreseeable risk given that state governments would have to bear the financial burden of managing and maintaining millions of acres of new land—and one way to relieve that cost is to simply sell the land off.

In addition, some legislators have drafted a variety of bills and resolutions aimed at dismantling our public land management agencies, making it harder for these agencies to do their job of maintaining public lands for multiple uses.

Instead of transferring our lands to the states and hindering our federal agencies’ ability to do their job for the benefit of all, we need to hold our government accountable to the will of the people, urge them to keep public lands in public hands, and craft legislation to protect our national heritage.

What you can do

Start paying attention to the areas in which you recreate. Do they have any form of formal protection? For what purpose are they managed and which agency is charged with their stewardship?

Let your representatives and senators know where you stand on these issues. Town halls, emails, petitions, phone calls, letters and postcards are all good options when trying to reach your elected officials.

When I started working for the Oregon Natural Desert Association in late 2015 to help establish a new long-distance hiking route, the Oregon Desert Trail (ODT), I started to pay attention—the trail was being created by an organization that has been working for 30 years to protect, defend and restore high desert public land in eastern Oregon.

I spent over six weeks in 2016 walking and packrafting the entire route, immersing myself in the solitude of these often over-looked mountain ranges and deserts, and talking with people I met along the way. I learned that this land is valuable for its remote canyons, rivers and mountains; it is valuable to the hikers, hunters, ranchers and all who live nearby.

In building the ODT, we had a unique opportunity to explore public land issues with recreation as the guiding framework. We created trail materials that educate hikers about the various land designations they’ll find along the route, including wilderness, wild and scenic rivers, and areas of critical environmental concern. The handouts explain why those areas are important, what their protections mean, and what our collective role is in advocating for their future.

It’s time for all of us who love to play in these wild and remote places to act to ensure we will be able to hike 2,000 miles, climb the high peaks, and raft the whitewater on our public land in the future.

Much of the current legislation that directly impacts recreation is on the state level. Information about state legislation can be found here: https://www.congress.gov/state-legislature-websites. On the national level consider: 1) Congress voted to repeal a Bureau of Land Management (BLM) policy called Planning 2.0, which provides for more public involvement, more transparency and faster results when it comes to making decisions about managing our public lands. 2) Bill 622 removes the law enforcement powers of the BLM and U.S. Forest Service. 3) House Joint Resolution 46 would make it easier to drill for oil and natural gas at 40 National Parks.

Author Bio: Renee Patrick has always placed more emphasis on having experiences and challenging herself than keeping a steady job and padding a bank account. This sense of exploration led her to join the Peace Corps after college, and hike her first long trail soon after. Eight thru-hikes and 10,000 miles later she is still in love with discovering her surroundings on foot and now she will be able to use all those experiences in her newest endeavor as the Trail Coordinator for the 750 mile Oregon Desert Trail. She will never stop hiking, and her favorite trail is the one she hasn’t hiked yet. Read more from Renee on her blog.

Author Bio: Renee Patrick has always placed more emphasis on having experiences and challenging herself than keeping a steady job and padding a bank account. This sense of exploration led her to join the Peace Corps after college, and hike her first long trail soon after. Eight thru-hikes and 10,000 miles later she is still in love with discovering her surroundings on foot and now she will be able to use all those experiences in her newest endeavor as the Trail Coordinator for the 750 mile Oregon Desert Trail. She will never stop hiking, and her favorite trail is the one she hasn’t hiked yet. Read more from Renee on her blog.