In the Footsteps and Handholds of Genghis Khan

Photos and Story By David Anderson

When Genghis Khan and his armies charged west across Mongolia on their way to conquer foreign lands, they traveled alongside a granite belt of mountains that stretch from central Mongolia to the Gobi Desert. They used these sacred granite peaks and outcroppings as landmarks to navigate by. On the western edge of the Gobi Desert lies the towering Eej Khairkhan Uul or Mother Mountain. These granite peaks have remained largely unexplored and unclimbed.

In a country composed of endless steppes and sprawling deserts, the people of the Mongolia have historically considered mountains and rock towers unique, sacred and worthy of protection. Historical legends tell the story of Genghis Khan scaling these cliffs to capture young eaglets for use as hunting birds. In 1709, Genghis Khan used his royal degree to designate 16 sacred mountains in Mongolia to be conserved and treated with respect for future generations. Logging, mining and hunting were forbidden in the mountainous regions that include Eej Khairkhan Uul and today these regions are part of Mongolia’s Natural Preserves.

Mountaineers have visited the high glacial mountains in northwestern Mongolia for the last 50 years, but few climbers have explored the alpine/rock climbing potential. In 2001, a five man British expedition climbed rock routes near the capital of Ulan Batar at Gorkhi–Terelj National Park. American Steve Schneider climbed a long alpine rock route near Central Mongolia’s highest peak Otgon Tengor in 2002 as well as establishing Mongolia’s hardest route in Gorkhi–Terelj. In 2010 a large group of climbers from Salt Lake City, UT established a number of boulder problems and single pitch routes in Gorkhi–Terelj.

In September, Szu-ting Yi, Lei Zou and I spent three weeks exploring and climbing in Gorkhi-Terelj National Park and Eej Khairkhan Uul. We repeated established routes and added several new routes. We also experienced logistic and access challenges and gained valuable information for climbers wishing to visit Mongolia in the future.

We flew from Beijing to Ulan Batar (UB) the capital city of Mongolia, where we stayed in a hostel near the city center. We arranged to hire a vehicle to take us 60 miles from UB to Gorkhi-Terelj National Park. We then visited the State Department Store and exchanged US Dollars for Mongolian Tugrik and discovered the nearby supermarket had almost all of the food products typically found in a Western supermarket.

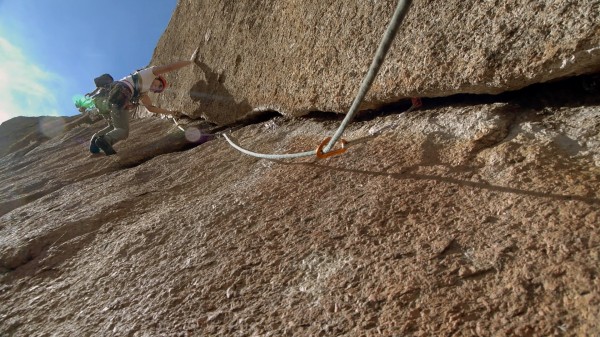

The park is a popular summer destination with many Ger camps (hotel-like set ups where guests sleep in tent-like structures). During the next few days we explored the granite spires and walls of the region. The rock is composed of large-grained granite reminiscent of that found in Vedauwoo, WY. We repeated some bolt-protected face climbs that were established by a group from Salt Lake City and local climbers.

We then set about trying to find natural crack lines to establish some new routes. After learning what to look for in terms of good quality rock, we established The Golf Ball Pinnacle I 5.9 R/X, Running Fox I 5.10 and The Red Dihedral II 5.10+. Overall this area has an incredible potential for single and short multi-pitch routes. With easy access, excellent accommodations and unrestricted route development, Gorkhi-Terelj National Park is Mongolia’s best rock climbing area.

Two days later, after paying excess baggage fees, (domestic air travel in Mongolia has a 15 kg total weight allowance for combined checked and carry-on luggage) we took off from Genghis Khan International Airport. The flight to Altai the capital of Govi-Altai Province was a smooth two-hour journey.

We touched down on a gravel strip to the north of the “city” of Altai amid snow flurries at 7,500ft in elevation. Altai consists of a couple dozen concrete cinder-block apartments, a few government buildings and several hundred Gers. We had tea at our translator’s house as they asked us unusual questions about the type of shoes we’d brought. Jargal said Eej Khairkhan Uul (Mother Mountain) was a dangerous place and suggested that we do not try to climb it. We decided to give it a shot anyway.

We went to local stores and bought three-weeks worth of supplies, loaded up the Land Cruiser and headed south toward Mother Mountain. The “road” was dirt and varied from smooth open steppes to bone-charring dry river drainages. Seven hours later we reached got our first view of Mother Mountain.

Legend says Eej Khairkhan was married to Aj Bogd a mountain located to the southwest. But Aj Bogd was old, his head was topped with white year round (covered in snow), and his wife was not happy. In the distance to the northeast she could see Burkhan Buudai Mountain. Burkhan Buudai was a younger mountain, standing tall and proud against the blue Mongolian sky. Aj Bogd’s wife could not take her eyes off of him. With each passing day she liked Aj Bogd less and felt more and more of an attraction for Burkhan Buudai. Finally she decided she must leave her husband to be with Burkhan Buudai. One night Eej Khairkhan awoke and decided tonight was the night to flee and be with Burkhan Buudai. Her husband woke up and saw his wife fleeing across the desert. In his anger he grabbed a big handful of sand and threw it at her. The sand landed on the bottom edge of her deel and held her down. She has remained to this day in her present location halfway between Aj Bogd and Burkhan Buudai. Her beautiful form lying alone in the desert brought comfort to countless lonely caravan men who could see her from far off and eventually she became known as Eej Khairkhan (“Mother Dearest”) Mountain.

From about 10 miles away it was easy for us to see the figure of a woman lying down in the silhouette of Mother Mountain – her head, breast and feet which contained the steep walls we had come to climb.

With the sun setting we set up camp at the base of the mountain. Jargal informed us that tomorrow the Park Ranger would arrive to tell us about the regulations of the park! This was the first time we heard of the existence of a Park Ranger.

In the morning we walked along a nature trail near our camp, seeing the nine sacred pools filled by a cascading stream, a monk’s tiny hermitage and various granite boulders carved by the rain and wind, which were said to resemble various animals. We were dismayed to discover the poor rock quality in this area of the park. The granite was very weathered, crumbly and there were very few cracks systems on the rock faces.

When the Park Ranger arrived he told us there was no climbing allowed in the park. We finally determined the reason for his reluctance to let us climb or explore did not have anything to do with potential damage to the resource or the Mother Mountain being a sacred area, the issue had to do with liability. The Park Ranger simply did not want to be responsible if we got lost or hurt at Mother Mountain.

Eventually, we convinced him to let us drive to the feet of Mother Mountain, just to take a look at the 2,000ft wall we wanted to climb. I was holding out hope the rock quality would be better 5 miles away. As we pulled up in the Land Cruiser my heart sank as I could see the rock was the same weathered choss.

It quickly became apparent that our expedition had come to an end before it even started. And I learned even the most carefully organized expeditions do not always go as planned, but the first hand knowledge you gain about the environment, the people and ultimately yourself is priceless.

Dave Anderson is a filmmaker, photographer, writer and explorer based wherever his van, Magic, is parked. Anderson has been climbing for 33 years and has established new routes in 10 countries on five continents. When not shivering during an unplanned bivy or editing his latest video in Magic, Anderson can be found leading climbing and trekking adventures in Asia with his partner Szu-ting Yi through their company LittlePo Adventures.