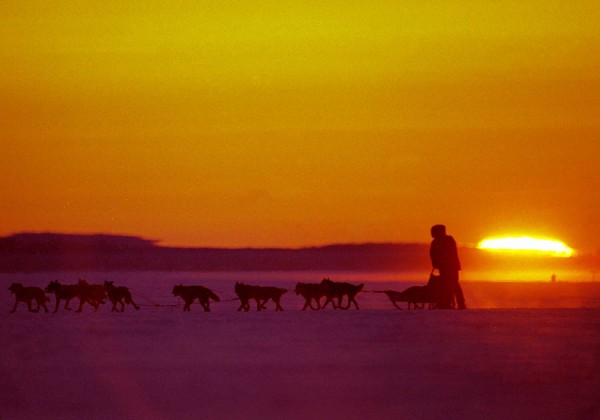

Eric Larsen on Dog Sledding, the Team Dynamic & Running with Your Best Friends

By Eric Larsen

In the fall of 1994, I was living in a remote cabin in northern Minnesota and working odd jobs. I stopped in a local lodge looking for work and was hired as a dog musher on the spot. At the time, I had never even seen a sled dog let alone driven an entire team of them. I dropped everything I was doing, drove 10 hours back to my parent’s home and grabbed as many base layers as I could find. For good measure, I rented the Disney movie Iron Will to glean a few pointers before my job started.

To say I was green is a complete understatement but after a month of ‘dry land’ training I felt I was ready for the real thing (famous last words). An early November snow meant we could finally hit the trail. Without a thick base, we would be pushing the conditions, but both the dogs and I were chomping at the bit to get on the snow. And while I had never run my own team before, it felt as if my whole life was building toward this moment. What could possibly go wrong?

I think about that first run every now and again – the dogs snorting steam and racing at full speed. Me hanging on the handlebars, getting dragged like a rag doll while careening off trees and large stumps, snow packed into every pocket and zipper opening. They say you’re never a dog musher until you lose your team, but somehow on that first crazy run, I managed to hang on to my sled and the team. Pulling myself upright after one particularly nasty spill, I realized my purpose: to become a dog musher. Over the subsequent 10 years, I traveled roughly 10,000 miles by dog team across much of northern North America on various training runs, trips, expeditions and races.

To better understand the fine art of dog sledding, you must first understand a little more about the dogs themselves. Remember, all dogs are descended from wolves. It doesn’t matter if it’s the biggest Great Dane or the smallest Chihuahua, each is bred for different characteristics. Many people are familiar with Alaskan Huskies, but that’s a breed that surprisingly doesn’t even exist. An Alaskan Husky is a generic term for any dog bred for the desire to run and pull. Alaskan Huskies are basically mutts. Some have long hair, others short hair. Some have blue eyes. Others brown. A few have one of each, but regardless of how they look, all possess that singular drive to run and pull. Harnessing that drive is equal parts art, patience and sheer will.

There is no such thing as a typical day with sled dogs; however, there is a typical routine that develops over time. In racing (which is my favorite type of dog sledding) each day begins early with a trip to the kennel for a feeding and general kennel clean up. Modern sled dogs are thoroughbreds, marathoners capable of covering 100 miles in a single day and just like a race horse, their health, diet and overall attitude are constantly nurtured and monitored.

Like any elite athlete, earning a victory at a race like the Iditarod is the result of years of preparation. However, training begins in earnest in the fall as temperatures begin to plunge toward freezing. Most mushers use ATV’s before switching to lightweight sleds as soon as there is enough snow on the ground to smooth out the trail. A training run can last anywhere from 10 to 50 or 60 miles.

The dogs run side by side and are attached to the sled by a rope called a gangline. Each dog wears a harness fitted specifically to the size and shape of the individual dog. All of the dog’s power is transferred to the gangline (and ultimately the sled) via another rope which attaches to the back of each harness called a tug line. A shorter, neck line, helps keep the dogs in place as well.

They say that if you’re not the lead dog the view never changes and for the most part that’s true. Each set of dogs has a specific role within the team. The two dogs directly in front of the sled are called ‘wheel’ dogs and are generally the biggest and strongest dogs. The two in front of them are called ‘team’ dogs and are the steady pullers. This is also where I often place younger dogs to gain experience. Depending on the race, mushers will add extra sections of gangline to increase the number of dogs running at any given time. For example, in the Iditarod, mushers will start with 16 dogs in each team. Right behind the leaders are the ‘point’ dogs and these are dogs that may be leaders at some point (because they are becoming more responsible) or are already leaders, but are not running out front at the moment. Lastly, the ‘lead’ dogs are the smartest and usually fastest dogs in the team and have a wide variety of responsibilities from keeping the gangline stretched out to understanding the commands for right ‘gee’ and left ‘haw’, among many others.

In mid and long distance racing, teams race Tour de France style, logging an overall accumulated time. Teams can choose to take ‘breaks’ at any point along the way, but most will try to reach a pre-established check point. A check point means food and rest for the dogs, but handlers and mushers have lots to do. A quick watery snack, remove booties, apply foot cream, coordinate vet check, feed a more substantial dinner, spread straw, apply wrist wraps and massage muscles, visit with each dog, and when they settle down to sleep, tuck them in underneath straw and a warm blanket. Since a typical race schedule is six ‘on’ and six ‘off’ for the dogs, mushers can expect to get about two hours of sleep for every 12 hours.

One of the things that I really enjoyed about running sled dogs was that no two situations were ever the same. I was constantly challenged physically but even more so mentally. The dogs, like people, have good and bad days and I was always intrigued to see how each of the dogs’ personalities complemented or clashed depending on their position, running mate, day, trail or situation. Rarely did I return to the kennel with the same ‘line up’ that I had left with.

I refer to my dog team and myself as we; but realistically, it is just them. After all, they are doing all the work. I just stand on the runners and try not to get in the way. But I do have a role in this endeavor and my winter ‘hats’ are many. I am the coach, doctor, friend, teacher, student, disciplinarian, dietician, and of course, humble servant. I know each dog’s personality, strengths and weaknesses more than I could possibly explain here.

Sled dogs are bred for their desire to run and pull and are most happy when running and pulling. Stop the sled for even a few seconds and they are barking and jumping in their harnesses. When the dogs are focused and working together their raw power is unparalleled. Day after day, week after week they give willingly to me everything they have.

But after 10 years, I am still left wondering why. Why do the dogs love running so much? Sure they like to go new places and see new things. Their senses, so much better honed to the environment than ours, must find every new smell a library of who traveled where and where. Still, as perplexing as their motivation might be, it’s hard not to put aside those deep thoughts and live as the dogs – enjoying every moment for what it is, feeling the miles tick steadily by and always, always traveling with your best friends by your side.