Bolting Climbs: The Ethics of First Ascents

I wiped the granite dust from my face on a sticky spring afternoon, watching my companion drill a hole in the rock. We were bolting a climb, eager to become “first ascensionists” at our favorite crag in North Carolina. Eight bolts after we began, we celebrated our victory. It wasn’t until much later that a pit began to grow in my stomach. Did acquiring a first ascent do anything more than pad my fragile ego? Was I becoming like the hordes of mountaineers that fight their way to the top of Mount Everest for a book deal? And what was the point of it all, anyways? I wondered. Evaluating the ethics behind first ascents begged the question of whether or not we’re creating safer climbs by “conquering routes”. Were we providing positive accessibility by bolting walls? Or just flaunting our abilities?

Why We Bolt Climbs

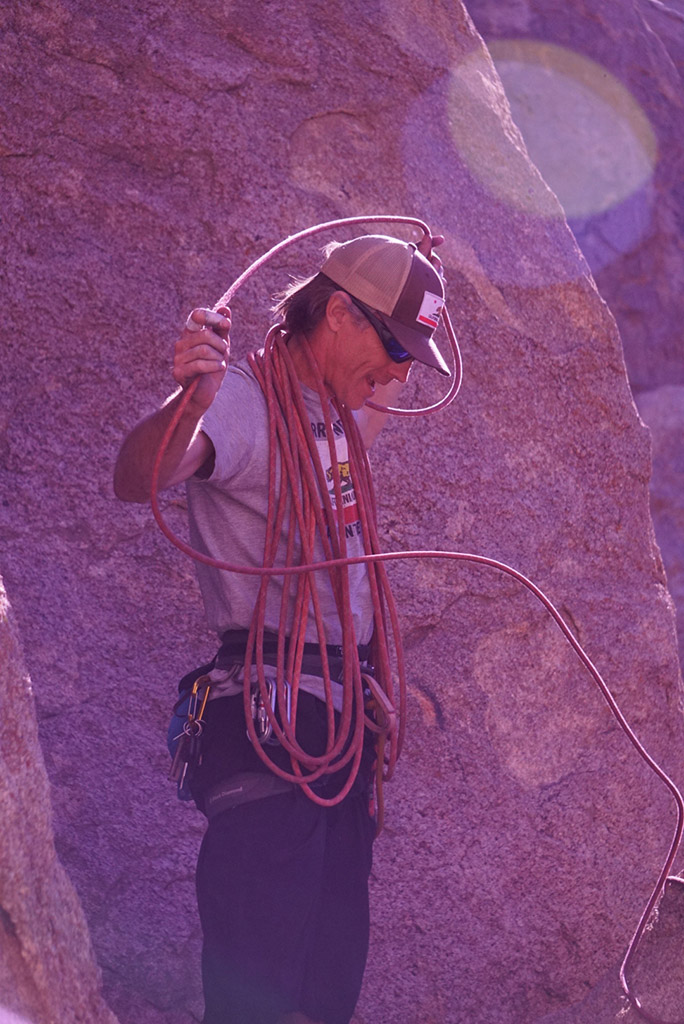

To get more perspective on first ascents, I reached out to Todd Gordon, a lifelong climber and resident of the Joshua Tree region. Known for exploring groundbreaking new climbs, Gordon’s reputation as a first ascensionist has earned him respect and legendary status in California. If you open up a Joshua Tree guidebook, chances are that you’ll find his name in it. A father and educator for most of his life, today Gordon works with climbers to create a safe and inspiring community.

I asked Gordon why first ascents and bolting routes appeal to him. “There’s something magical about finding a path to the top of a feature that’s largely untouched,” he explained. “When climbing pioneers set out on a route for the first time, it’s not entirely clear whether or not a line is possible.” Climbing a route for the first time provides a rare pioneer experience in a world that’s largely discovered. Although the reasons for setting routes are variable and ever-changing, there’s an element of exploration that keeps climbers coming back to fresh rock.

Climbing hardware and rope systems were originally developed by Europeans in pursuit of bigger and better routes. Brought to Yosemite to increase the scope of what a climber could accomplish there, these systems allowed climbers to make it to the top of iconic features like Half Dome and El Capitan, changing the history of climbing forever, and most believe, for the good.

To Bolt or Not to Bolt

But today, an uptick in climbing’s popularity has the potential to contribute to ecological and environmental damage. If the recent demand for indoor climbing gyms offers any indication for outdoor climbing growth, the boom is exponential. Between 2009 and 2017, the number of US climbing gyms went from 13 to 43. In 2017, the Outdoor Industry Association showed that the past decade has seen substantially more people heading outdoors. Bolted routes attract crowds. And more people equals higher impact, which contributes to issues like accumulating garbage and human waste, soil erosion and habitat disruption. Is creating more accessibility to new crags always a good choice?

Additionally, if a route can’t be climbed without bolts, should it be considered a viable route? Many climbers agree that a route should be climbable on gear alone. Adding bolts just enhances the safety of that particular route. But some climbers don’t want to tarnish the rock by adding bolts. Others approach bolting as a minimalistic activity. In areas like North Carolina, the climbing style is predominantly traditional. The bolts exist but they’re run out (few and far between) and you’re likely to hit the ground if you don’t bring the right gear. Even if you do bring the right gear, falling in the wrong place can be catastrophic or even fatal. But many locals believe that the rock shouldn’t be bolted if it doesn’t have to be; it generally takes gear well and there’s no reason to sully another crag. But these choices can add to the danger that’s associated with repeating a climb if they push subsequent climbers’ gear to the limit. So is it ever irresponsible to leave a climb unbolted?

A case study: In 2014, Matt Segal was climbing in Liming, China when a first ascent ‘found him’. While scoping out a new route, Segal determined that the climb could be completed solely on gear. He was able to find two small placements in a 5.13+ section. While leading this route, he took a fall from about six feet above those small placements. His fall was so violent that he pitched himself over the edge with his head facing the earth. The rock crumbled around his gear, leaving him free-falling to his next placements. Luckily, his lower placements held, arresting his fall. But he’d plummeted 45 feet, barely preventing impact with the ground. If more gear had blown he would have landed on his head, likely causing his death. The experience helped Segal to determine that a bolt was necessary to prevent a fall like the one he’d taken—even if it was possible to climb the route on gear. The resulting route was named Air China (5.13+ R).

To some extent, the first ascensionist has authority over the level of risk that future climbers take. When asked if a route should be bolted if it could keep climbers from dying, “Yes,” was Gordon’s enthusiastic response. “If these routes are really dangerous and you fall and kill yourself, I used to say that’s your responsibility. [But] a lot of these older guys realize that life is more precious than your ambition and climbing.”

How to Set Safe Routes

It’s curiosity for the unknown that drives many first ascensionists, including Gordon. “When you see these new routes, you don’t know where they’re going to go, or where the bolts will go or if the protection is good,” he explains. “There’s this whole big curiosity… People love the unknown and the adventure.” In an era where most wilderness areas are no longer wild, becoming a first ascensionist gives climbers the ability to discover new rock potential. If you’ve evaluated the pros and cons of bolting a route and decide it’s the right move, make sure you do so responsibly. Part of that unknown of a new route is determining correct bolt placement, which is a combination of art and science.

It’s critically important to seek mentorship or spend a lot of time in the outdoor climbing community prior to bolting a route. Doing so can keep you from making embarrassing or dangerous mistakes. A code of ethics for bolting climbs does exist. For example, in most cases, climbers don’t bolt cracks. Cracks usually take gear well, which should make a bolt unnecessary. You should also think twice before bolting in ecologically sensitive or already highly impacted areas where an increase in human traffic would be detrimental. For more information on bolting ethics, click here.

First ascents require confidence, expertise and grace, which are qualities that climbers build over the course of time. Determining whether or not it’s safe for you to claim a first ascent can simply be a matter of experience. Gordon asks, “How long have you been climbing? If you’ve been climbing for three or four years, you shouldn’t be bolting. You’ve got to put your time in.” Learning where and how to set a route is an intricate process that requires expertise that’s gained from experience. But in his salty climber fashion, Gordon added, “Every generation gives a finger to the generation before them sooner or later.”

Related Posts:

- Multi-Day Rock Climbing: To Stove or Not to Stove

- Tips for Your First Alpine Climbing Trip

- Why Rock Climbing Needs More Female Guides

Mary Beth Skylis

Mary Beth Skylis

Mary Beth Skylis has been lucky enough to begin her life of outdoor pursuits on long trails, hiking the 2200-mile Appalachian Trail, the 458-mile Colorado Trail, and part of the Annapurna Circuit. She has feasted her eyes on the snowy Himalayan peaks, watched aggressive rhinos contemplating a charge, and observed Costa Rican monkeys leaping through the air. Skylis has been on the sharp end, wondering why we put ourselves on the edge of our comfort zone only to launch ourselves into the abyss time and time again. Yet, she doesn’t think she’ll ever return to the comfort of routine. When she isn’t adventuring, she can be found collecting personal narratives and adventure stories for those who need their outdoor fix. Her work can be found in Backpacker Magazine, Outside Magazine, and Yoga Journal. When she isn’t telling stories, she can commonly be found on an airplane to nowhere or in the steep and jagged mountains.